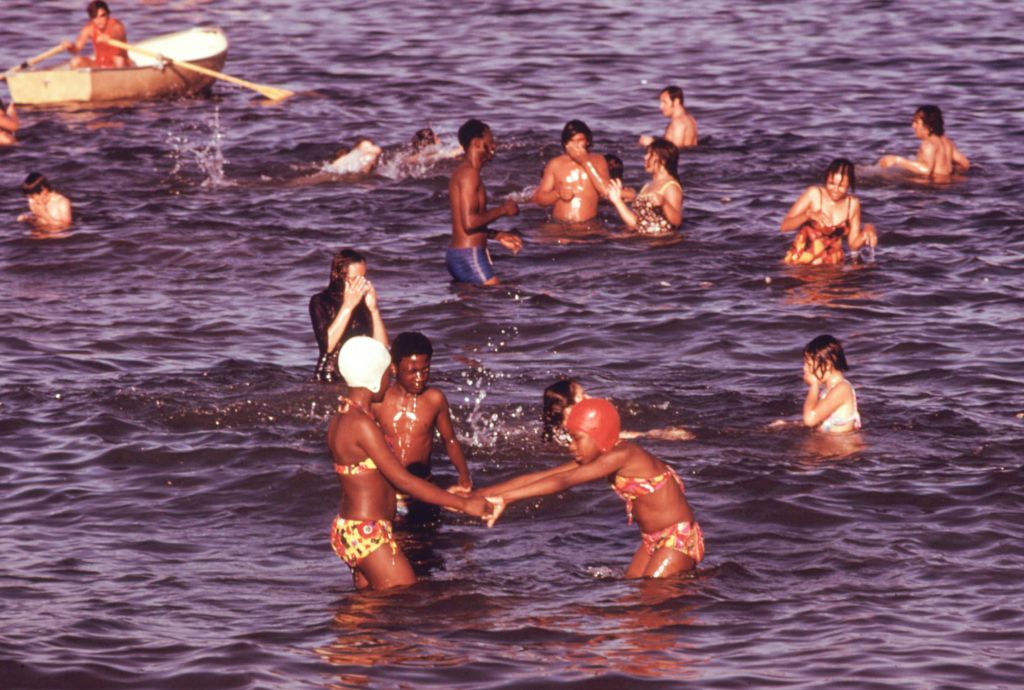

Source: Jeff Greenberg / Getty

When I was young my father would talk to my brother and me about his parents. The only television in the house, often the sole source of light in the room, would be turned off creating a quiet mood. Those instances were sacred. My paternal grandparents passed before my birth and my maternal grandparents died soon after. As the years have passed, I began to recognize that those talks were opportunities for my father to express his love for family, to demonstrate grief and share our history. At the time, however, they would shake me to my core.

A youngster with an active imagination, I would go to bed frightened after his talks. The details conveyed to me symbolized the lives of a distant past. I could envision my grandparents’ clothes and faces vividly based on the pictures I found in photo albums throughout our home and my dad’s descriptive storytelling. Bringing their memories to life left me wondering about their spirits and in my bed, at night, the lingering presence of my father’s stories haunted me. I would envision my grandfather working in loud, smokey, crowded factories in the ’40s and ’50s, decades before I was a thought. I could feel my grandmother’s energy coming home after a long day of work—a repetitive act of dedication, fatigue and joy.

My fright stemmed from the lingering questions in my head. How could anyone work in a factory alongside people who were losing their fingers when large machines malfunctioned? Was it really possible for both of these people and so many others in the past to work themselves so hard that they died so young? These are the questions that speak to the everydayness of Black struggle, not the spectacular aspects the American public loves to remember. It is easy to forget that the fight for equity, and life, extended beyond the protest line. I was unable to comprehend the past, their pasts, and the daily heroism my grandparents displayed. But that was then.

It is easy to forget that the fight for equity, and life, extended beyond the protest line.

My fear of grandparents’ ghosts eventually dissipated, but I picked up new terrors when I got older. I entered college and pursued a major in history. One of my courses was titled “United States History, 1914-1945.” The professor, a favorite of mine, made it a point to emphasize the American tradition of imposing racially discriminatory policies. Once, when my classmate, a white woman, raised her voice in objection against the lecture, she went into a passionate rant about how her grandparents, European immigrants, worked hard to pursue the “American dream.” Her talking points mirrored the prevailing narrative shaping how so many people in the U.S. come to think about history, race, immigration and citizenship: that white people came here for a better life. In her mind, white people faced discrimination, too, but according to her, they have been able to find work, create families, pursue educations and develop healthy communities.

My classmate’s face was red with frustration as she proclaimed that her white immigrant family worked hard and never complained. Because of their hard work, she believed that is the reason she became a college student. The implication was clear—that the existence of a history of white supremacy in the U.S. was not connected to the inequitable conditions shaping the experiences between whites and people of color in the course. To her, Black people are lazy. “We simply did not work as hard.”

As the only Black male in the class, I had likely served as evidence to this student that people of color were in fact unqualified instead of the more logical reality that Black students face multiple obstacles, which prevent us from having access to higher education. And even if we do enter higher ed institutions, attaining a degree remains difficult due to systemic issues that prevail in education. At the time, however, I remember being unbothered by her outburst. In fact, no one, except my nervous professor, was. Surely her perspective was outdated, as old as her own grandparents.

My thoughts were that in our Black future, we would not need to contend with her thinking or lack of insight. I was wrong. She likely was able to celebrate the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as an exceptional hardworking negro while upholding the belief that the rest of us were lazy niggas. The disconnect between Black History Month as a moment of reckoning with the deep roots of systemic racism, and the anti-Blackness that takes roots in some of the very people who love to quote King, is caused by our love for exceptional Black stories. But Black history is about the exceptional nature of Black survival, writ large.

The disconnect between Black History Month as a moment of reckoning with the deep roots of systemic racism, and the anti-Blackness that takes roots in some of the very people who love to quote King, is caused by our love for exceptional Black stories. But Black history is about the exceptional nature of Black survival, writ large.

Too many of us now believe that the Black people we ought to celebrate are those who’ve offered extraordinary contributions. Yes, highlighting the work of the Dr. King provides us with a resume of one whose accomplishments catalyzed change, but he did not do the work alone. King was one of countless southerners, northerners, preachers, activists and community members working to change Jim and Jane Crow laws.

Yes, Oprah Winfrey’s show broke records in the media industry, but there are also countless people and organizations who have been working on issues of racial justice in media. Ida B. Wells was just one of the persons. In a white supremacist society, our belief in exceptional historical figures creates a particularly interesting dynamic. It can often foster the idea that only a few African-Americans are, in fact, worthy of acknowledgment. The reality is that living, working and loving as a Black person in America has always demanded an exceptional existence.

Source: Smith Collection/Gado / Getty

Stanford’s Center on Poverty and Inequality reported in 2017 that racial disparities in health, employment and wealth remain pervasive. “For every dollar of wealth held by the median white family,” the report states, “the median African American family had less than 8 cents in wealth.” The premise of the report is that survival remains radically unequal for white and Black Americans. These are the normal, abnormal conditions that devalue Black lives, disenfranchise Black communities and literally kill Black people sometimes expeditiously through lynchings but more often slowly through chronic trauma.

In the article, “Slow death: Is the trauma of police violence killing black women?” writer Cristen A. Smith asks, “If we as a nation want to truly address the problem of anti-black [violence], then we must shift our national discussions from simply tallying the body count of the immediate dead to assessing the traumatic and long-term deadly effects on the living.” This is one of the foremost moral and political questions America has yet to contend with. Any Black person alive today, this Black History Month, has survived slow or expeditious deaths. We live despite the incessant specter of death sometime meted out by vigilantes, law enforcement, or other instruments of the state.

The stories we tell this month and in the days and months beyond are important. They should extend far beyond the material productions and socio-political contributions of folks within our communities. Thankfully sites like The Black Inventor Museum do the work of illustrating ideas and productions of Black people in America while the National Museum Of African American History And Culture are able to also provide multi-layered accounts of our collective existence in the U.S.

Black History Month is not about exceptionalism.

Black History Month is not about exceptionalism. My father’s practices and those of my classmate are examples that the everyday stories we tell about the people who make our past have deep impacts on how we view the present. Due to trauma largely inflicted by racism, our stories can be harder to share, but we must find a way to do so by recognizing that our Black lives matter simply because we exist. This month, and every day, we must share the history of our existences, that of our families and all Black people. Our future depends on it.