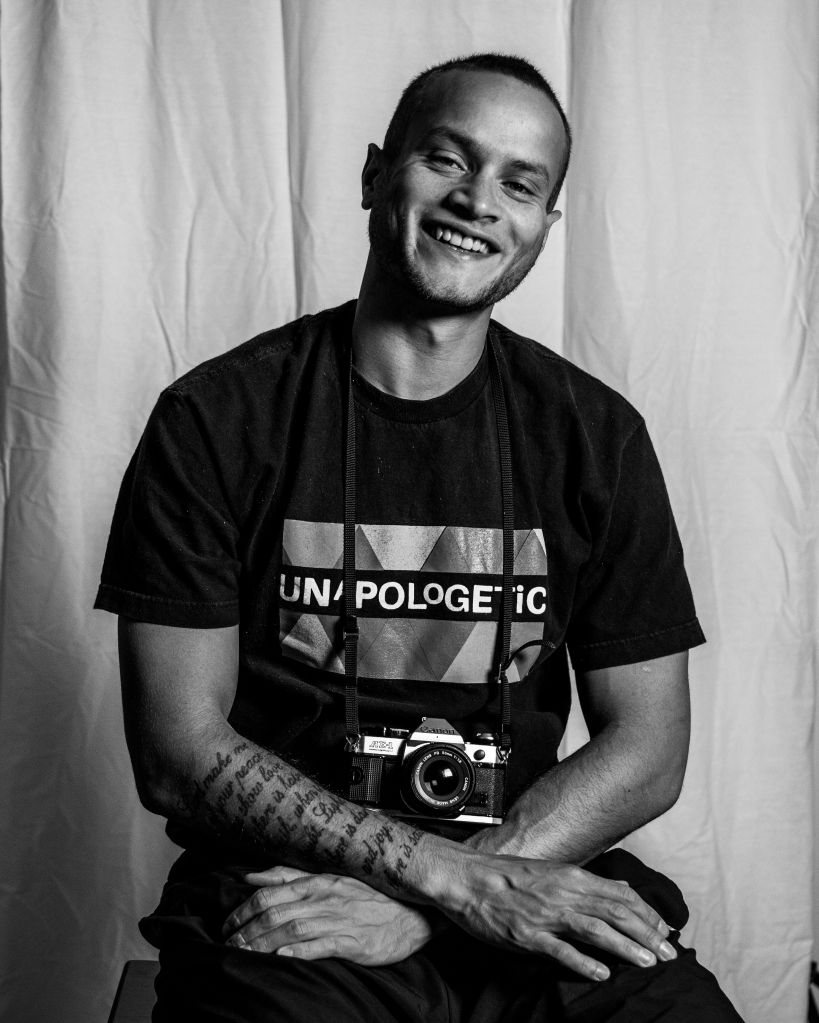

Source: Rob Liggins / Rob Liggins

During the summer of 2020, during a global pandemic and after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, protestors throughout the United States (and the world) took to the streets to demand the end to police and white vigilante violence against Black people. We had had enough. Enough of a governing body that created rhetoric and policy that was racist, sexist, homophobic and xenophobic. Enough of an administration that shunned science and mishandled a pandemic that disproportionately harmed us. Enough of more than a century of promises for progress that seemingly never came. These moments radicalized Los Angeles based documentary photographer Rob Liggins to grab his camera and join protestors, hoping to tell a more authentic and more inspiring story about the Black Lives Matter Movement than he was seeing in the news. We caught up with Liggins to discuss his life, his passion for telling Black stories through photography, and the joy of documenting protests.

CASSIUS presents Young Black Icons

Let’s begin by chatting a bit about your origin story. Where are your from? How did you find your way to Los Angeles, and how did you find your way to the camera?

I was actually born down in New Orleans, Louisiana. I lived there for the first few years of my life. My dad was in the military, so we moved to Oregon when I was pretty young, and that’s where I grew up. I went to school in the Portland Metro area. I wasn’t really into photography at that time. I was mostly into playing sports. I played basketball my freshman year in college, but I ended up messing my back up. In hindsight, I guess that was a good thing. I went to Portland Community College, then I transferred to the University of Oregon where I majored in communications. While there, I was taking an intro to communications class, and one day we had a guest lecturer named Leonard Henderson who was trying to get students to enroll in his two-day lighting video workshop. I couldn’t wait to sign up for the class, not because I knew anything about photography or videography, but because he was Black, and I had never taken a class from a Black teacher or professor. I don’t know how much you know about Oregon, but it is a very, very white state. I was really just excited to be able to learn from Mr. Henderson and have that experience.

Once in the class, I just focused on having fun. And Mr. Henderson was very encouraging. He became, and continues to be, a great mentor in my life. He would give me guidance, tell me what I was doing well, and he offered to be a resource for me—to be honest with me about my work good, bad or ugly. To this day, when I update my website or when I create new work, I send him links.

It’s amazing the kinds of brilliance that can be unlocked in Black folks with a little nurturing and guidance, and this is such an important example of how imperative it is to cultivate Black creativity through having Black mentors and Black teachers. So, you continued studying videography, and what came next?

After I finished my studies at University of Oregon, I moved to Los Angeles and got a job in advertising. The agency I worked at had me doing a lot of copywriting and video work, and during my off time I started picking up my camera and just shooting—like a little hobby. I was working on bettering my lighting and composition skills, but I wasn’t thinking too deeply about becoming a photographer. At my day job, I met another person who became a mentor to me—Brandon Viney. In my ad work, he’d encourage me to really search for my own meaning in the videos I was producing. When I’d turn assignments in, he’d say things like, “It seems like you’re trying to make me happy with this.” He encouraged me to find and center my own voice in my work, and that helped as I was developing my voice and skills in photography, too. He’d tell me he felt there was more to me than I was sharing, and that I needed to tap into that and not be afraid to be fully who I am, even if some people won’t accept it.

So, the journey began towards finding your voice, and you started shooting more photographs. What made you interested in becoming a documentary photographer and capturing everyday life Black Los Angeles?

So, there’s this quote that I think really sums up why I think it’s so important to capture people’s everyday lives in my work. It’s from Viola Davis’s acceptance speech, when she won the best supporting actress Oscar for Fences, and she said that being an artist is the only profession that celebrates what it means to live a life and what it means to be a person. Of course, Viola Davis was talking about acting and filmmaking, but it applies to photography and all art. I want to celebrate simple, everyday life, and all the bounty that happens in those moments. These kinds of moments are so overlooked and underappreciated. That underappreciation is what helps inform the kinds of stories that I want to tell. In representing Black life and Black stories—whether in music, photos, whatever—I think the everyday joy and the everyday life of Black people is sort of skipped over. It’s not seen as much as an attention-grabbing story as the trauma of Black life is. I want to change that. I want to capture the whole experience.

You speak about the importance of capturing Black joy. In viewing the photos you captured while protesting throughout the summer, in so many of them, there is an air of joy—even in these moments of anger and frustration and sadness. Why was capturing moments of joy such an important part of documenting the protests as a whole?

To me, this ability to hold on to joy, in all of these different kinds of circumstances, is one of the core elements of being a Black American. It’s one of the things that makes us so special. And, so, I always want to tell that part of our story. If someone doesn’t include that part of the story when they are capturing the lives of Black people—they aren’t committed to telling the whole story. I’ve learned that you have to put out the energy in the world that you want to see, and I think, especially through this year with everything that is going on, capturing joy in those destitute moments gives people hope. When hope is lost, it’s harder for us to fight and it’s harder for us to win. There’s a quote that I always think of while doing this work from the abolitionist Mariame Kaba, where she says that hope is a discipline. It’s something that you have to wake up and practice every single day—and like other disciplines there are going to be times when you feel like you’re not good at it. The work, really, is learning to stay disciplined in being hopeful—especially as we face things that seem insurmountable like police brutality and racism.

Hope is a discipline; I love that. Who might you say has given you hope in this fight? Who have been an inspiration for you to protest and to fight for Black lives? Who are some activists and creatives that inspire you as you continue to do this work?

I’d have to begin with my parents, Reggie and Julie Liggins. They always just wanted me to be politically aware. At home, my father would have the news on in the way some people watch Sports Center. So growing up, I began to ask questions and slowly learn the importance of being aware of what is happening in the world. But mostly, my parents instilled in me the importance of being a part of your community—of working in your community. I grew up seeing my mom constantly volunteer for all kinds of causes. I grew up being very active in the church with my siblings, too. We were always carrying tables and chairs and setting things up and breaking things down—and that has always kind of stuck with me. Be a part of your community. Offer to help do the work. Jump in. Carry some chairs.

I am also grateful to watch the work of local organizers that are a part of BLMLA—Dr. Melinda Abdullah, Joseph Williams, Kahlila Williams, Janaya Future Khan, Kendrick Sampson and so many more. As far as creatives activists, I would say James Baldwin inspires me, and Angela Davis and Zora Neale Hurston. I actually named two of my cameras Jimmy and Zora. I also have to add, of course, Gordon Parks. As far as photographers who are shooting now, Devin Allen who did the work of documenting protests after the police killing of Freddie Gray in Baltimore has to be on the list. And there’s Laylah Barrayn, Michael McCoy, Dee Dwyer, and so many others. I also have to add my great uncle Warren Hodges, Sr. to the list of inspirations. He’s like the family archivist. He has done all of this research about my family. He has researched and collected photographs of our family that go all the way back to Reconstruction, and I’ve learned so much about telling and preserving stories from him.

I’d like to end our chat by asking you what advice you might give and upcoming artist/activist. What advice do you have for young creatives?

I’d say—first of all—that you have to make the stuff that you want to see in the world. Nowadays a lot of creatives for instance, are coming up in the age of Instagram and other social media, which makes it really hard not to self-compare and shift your work to what you see from others or what you think people want to see from you. It’s like, you feel like you have to focus on beating the bullshit algorithm, instead of focusing on the art you want to make. You have to constantly ask yourself, “What am I not seeing in the world?” or “What do I want to see more of in the world?” and just keep going until you produce that work. Also, find five mentors. Find the people who are making the art similar to the art that you want to make, and reach out to them, if you can. You’d be surprised how many artists want to share their knowledge and experience. I definitely am open to mentoring those who are trying to find their way. My mentors always told me that when I make it—they don’t want gifts, watches, none of that. They want me to pay it forward, bring the next one in. And I really try my best to be committed to doing that.

You can connect with Rob Liggins via his website or on Instagram at @robliggins.

Josie Pickens is an educator, writer, culture critic and community organizer. Find her on Twitter and Instagram at @jonubian.

Click here to learn more about Cassius’s Young Icons. They’ve got next.