Source: iOne Creative / iOne Creative

During Black History Month, the narrative is typically constructed to highlight Black people who have achieved greatness. But it often leaves those who also identify as LGBTQ+ and gender nonconforming out of the conversation. This year, CASSIUS disrupts the mundane by highlighting Black queer and trans luminaries whose lives and work deserve celebration.

Emile Alphonse Griffith was born in 1938 in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. He was one of eight children being raised by relatives while his mother found work in New York. She sent for him when he was 12.

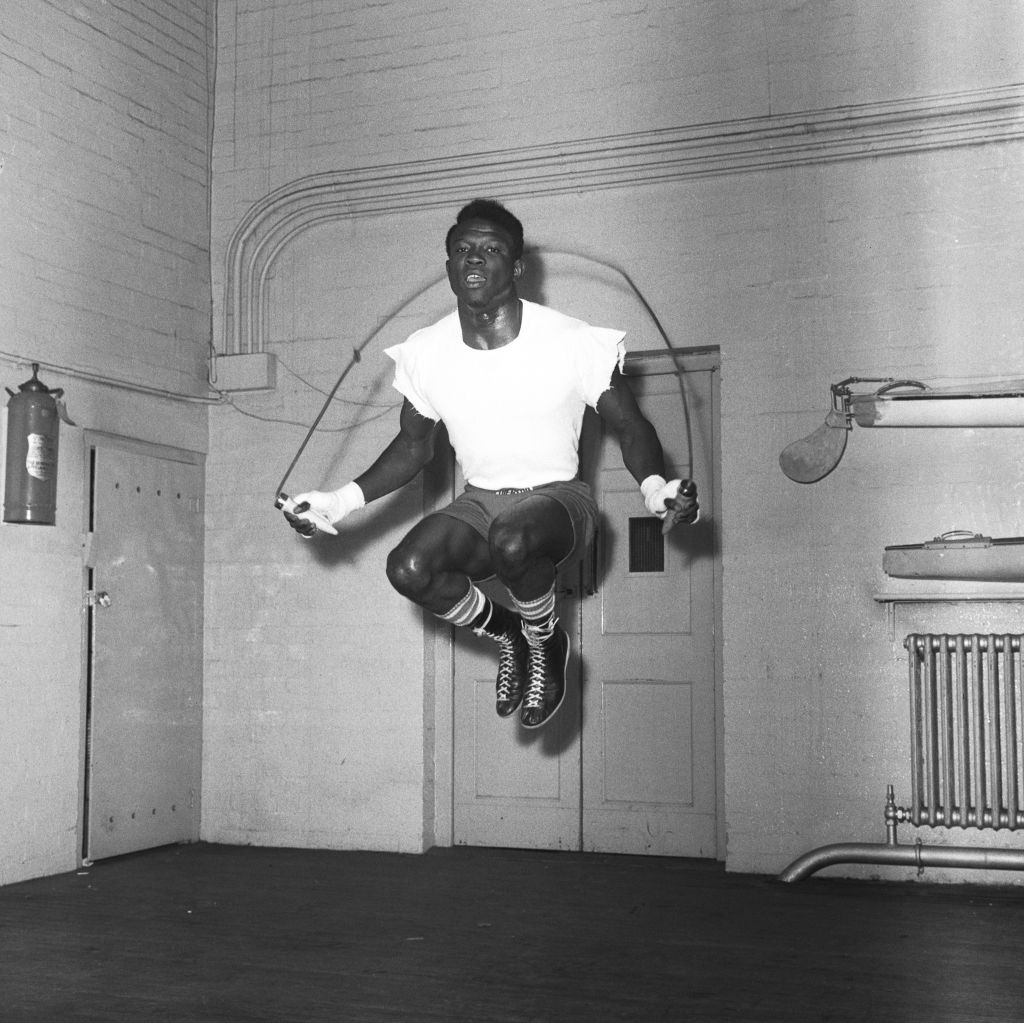

It didn’t take long for Griffith’s destiny to be fulfilled from there. He took a job at a garment factory whose owner was a former boxer. When he saw Griffith’s frame with a narrow waist and broad shoulders, he sent him to boxing trainer Gil Clancy. By the time Griffith was 20, he was the Golden Gloves champion at welterweight and turned professional.

Unfortunately, most of Griffith’s legacy is overshadowed by his relationship with the man who became his rival. In 1961, Griffith beat Cuban boxer Benny “Kid” Paret in their first match together. At the weigh-in for the rematch six months later, Paret fixed his mouth to call Griffith a name that would be part of a major turning point in both of their lives: maricón, which is Spanish for f*ggot.

“Hey maricón,” he said, wagging a finger at Griffith. “I’m gonna get you and your husband.”

At that time, homosexuality was considered a “psychiatric disorder” and a crime. Consensual sex between two adults of the same-sex could result in imprisonment. While it was an open secret that Griffith visited gay bars and stopped to talk to the trans women sex workers on the streets of Times Square, he knew it would ruin his career if he came out publicly.

Griffith tried to step up and swing at Paret after he uttered the slur, but they were broken up before anything could happen. Later that night, he lost the rematch by a disputed split decision.

Source: PA Images / Getty

But on the night of March 24, 1962, everything changed. Another televised welterweight title fight between Griffith and Paret took place. This time, Griffith did not hold back. He relentlessly packed every bit of rage, hurt, and trauma into his assault on Paret’s body, each punch landing on him with deadening force. By the time the referee, Ruby Goldstein, stepped in, it was too late—Paret was out cold.

“The right hand whipping like a piston rod which has broken through the crankcase, or like a baseball bat demolishing a pumpkin,” Norman Mailer, a ringside witness, recalled the fight in an essay.

Paret had blood clots in his brain and passed away 10 days later at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City.

The governor of New York at the time, Nelson Rockefeller, ordered an investigation, which cleared both Griffith and Goldstein of blame for Paret’s death. Goldstein never refereed another fight and the ABC network dropped primetime boxing for the next 20 years. Griffith was haunted by nightmares and claimed he was never as aggressive again as a fighter.

“After Paret I never wanted to hurt a guy again,” he told Sports Illustrated. “I was so scared to hit someone, I was always holding back.”

Otherwise, Griffith went on to live a normal life. He got married in 1971, only to get divorced less than two years later. He coached on the side before working as a corrections officer in New Jersey, where he met Luis Rodrigo, his partner. It wasn’t until 1992 that his sexuality was pushed to the forefront again when a gang jumped him after he left Hombre, a gay bar in New York. The beating left him near death.

I kill a man and most people forgive me, however, I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person

In a 2005 TV documentary about Griffith called “Ring of Fire,” he talks about that fated night in the ring. He told The New York Times he got tired of people calling him a f*ggot.

In a hypermasculine sport like boxing, where hands are literally being laid on men to inflict so much harm as to render them unconscious, it was a taboo for Griffith to want to lay hands on a man in love and tenderness to heal. As his brain deteriorated from dementia, he uttered the most profound statement: “I kill a man and most people forgive me, however, I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

We lift up Emile Griffith in the spirit of all those who have suffered at the hands of toxic masculinity, today and always.