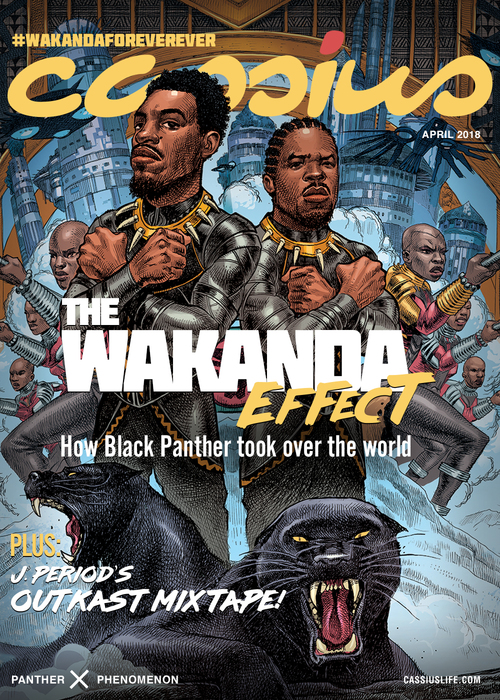

Source: Dan Lish / iOne Creative Services

Atlanta is a string so taut it has become a metaphor for Blackness. For the impossibility of it and the way, it returns, triumphantly, to each bland moment with something else to give it. Always something else. Maybe because we’re mythic.

“I’m not real. I’m just like you,” Sun Ra said in Space Is The Place. “You don’t exist in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You’re not real. If you were, you’d have some status among the nations of the world. So we’re both myths. I do not come to you as a reality; I come to you as the myth, because that’s what black people are. Myths.” We are myths because we are always seen drunkenly through the gaze of others. So when we claim a space for ourselves where else can we really go? To Stankonia then or to Wakanda? To where Gucci Mane said everything is yellow like the V-Cuts? Or maybe you listen to Big Boi and 3-Stacks come with the weather; maybe you let OutKast look out at you, arms crossed in front of their chests and welcoming you home.

So when we claim a space for ourselves where else can we go? To Stankonia then or to Wakanda? To where Gucci Mane said everything is yellow like the V-Cuts?

On Twitter, there are all kinds of hashtags for the things Black people can’t do. #Workingoutwhileblack is one after two tired Black men got questioned and then kicked out of an L.A Fitness in Secaucus, N.J. for being a myth. #Drinkingcoffeewhileblack because two tired black men got arrested for being a myth in a Starbucks in Philadelphia. The worst part is, of course, that Starbucks is always filling their haunts with jazz, performed by the artists who were met with “White’s Only” signs whenever they sought out a fresh brew. Then there’s driving while Black and standing in your backyard while Black. There’s minding your business while Black and being a woman while Black. Don’t forget being queer while Black or being trans while Black. It gets to be too much. You are always aware you are an alien; that you are foreign here, in the land of your foremothers. Or maybe you listen to J. Period drop breadcrumbs for you to follow; maybe you press play a sonic hajj into the wilderness of music.

OutKast claimed our home in the Dirty South. “Jazzy Belle” was Andre’s. “Oh yes I love her like Egyptian,” purred out of him and you knew that he was special. That this group was special. That Atlanta was some great pyramid where the slaves found themselves alone one night and looking up at the stars. The first time I’d heard it I was 13 or 14. I’d snuck into my sister’s room looking for tapes. I dug and dug and stumbled on ATLiens. Clutching the CD, visibly tip-toeing like a thief, I hurried back across the hall to my own corny room, the walls sheathed in wooden panels from the 70’s. I lay down with ‘Kast and heard the aural version of my searching: “Elevators (Me & You).” Obviously, I was transfixed, and between the eerie beats and the earnest rhymes, I was following a path to a kind of home. Maybe Wakanda, or maybe Stankonia? The cover art for J. Period Presents… #WakandaForeverEver lands 3-Stacks and Big Boi in our newly claimed Afro-futuristic home, in full salute, welcoming us to safety and full understanding.

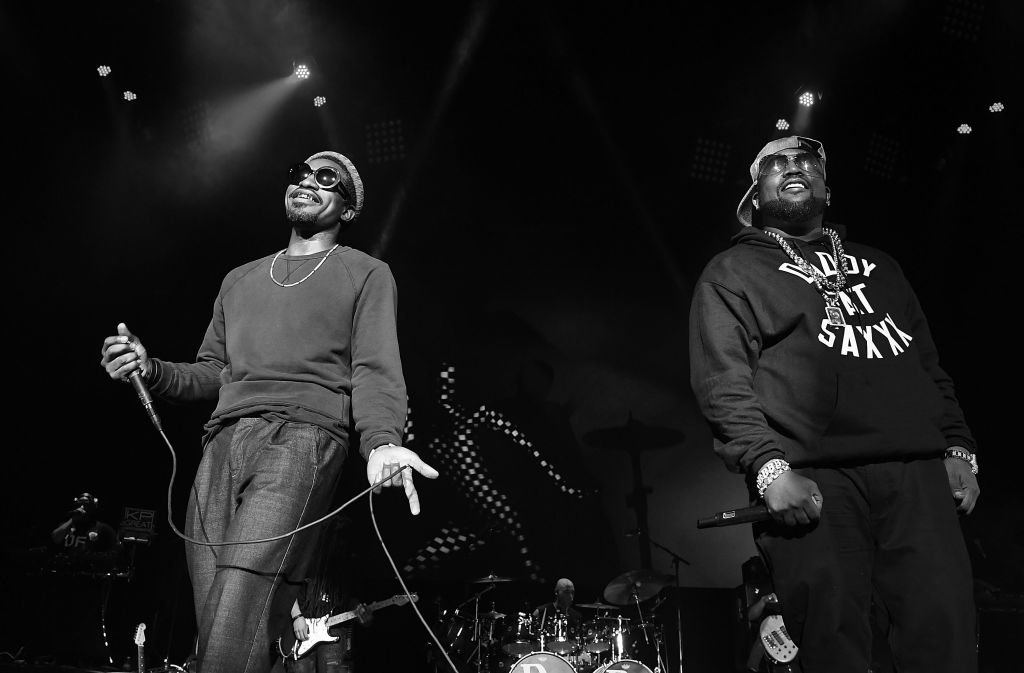

Source: Paras Griffin / Getty

Wakanda wasn’t even a glimmer I’d managed to feel in my life. I’d never considered a home like that one. My father would tell me, growing up, that your enemies in Jamaica are Black, too. And when I was eight once I wandered too far and found myself surrounded by a roving pack of dogs I paused but soon set out in a sprint. One monstrous bite into your calf is all it takes to wake you from your sleep of safety.

Even with the dogs, Jamaica is my home. It’s where my grandmother built our little house on our little block. It’s where my cousins are and nieces. It’s where I am at five years old, watching Chuck Norris murder terrorists on our small technicolor television. My grandfather’s there, too, smelling of rum and smiling toothlessly into the universe. My ancestors are buried there, a short line of the whipped, the escaped, the murdered, and the winged. Where Yankees think your entire life is, “Can you whine?”

An immigrant, I am robbed of both worlds and enmeshed in them, a shapeshifter in the sunlight, a mythic monster to the police and a baby to my mother.

It is a world set apart from the Western tourists who visit our world-class beaches. Those aren’t the beaches we go to. Our sand is a muddied pool, the darker the better, suffused with rocks, with water so salty that when you walk in with a wound, you walk out with a scar. It’s where I am, too, a stranger. An immigrant, I am robbed of both worlds and enmeshed in them, a shapeshifter in the sunlight, a mythic monster to the police and a baby to my mother. I am a gasp. Yet, I have never been to the continent. Instead, I have had Uber drivers tell me they’re sorry for what our common ancestors did. They are Homo Sapien, then. I am something else.

I know because in the UK they’ve been deporting my bredrin for years now. After WWII they said come with and rebuild the world of your tormentors. My bredrin went and did. When the Empire Windrush landed at Tilbury Docks, off came smart looking boys and girls, grown, with tunes on their tongues. Now, the weather’s changed. The diaspora is Britain. We’re in the grime and in its words. We’re in the novels and the sculptures — the theatre, too, if you can imagine — and they’ve had enough. Now my people are ATLiens. Where are your documents, they ask. This is our NHS, not yours, they say. As if our common ancestors knew anything but work.

J. Period’s revisioning of the space between Wakanda and Stankonia, then, is really a pilgrimage to discover yourself. That concept — the self — was a contentious one in my house. One of those heebie-jeebie ideas my parents waved off as “American.” To them, you were your parents, and you were your children. It was their job to teach you to “make life,” and it was your job to make it. They didn’t have time for you to be a “teenager” or a gadfly. That kind of thinking would make pugilists out of my sister and me, but every once in a while you’d see the music hit them and they’d drop the facade to dance. They’d go home, somewhere, to a city inside of themselves they shared. The way OutKast makes your Afro-future a possible future.

Like the way you leave Black Panther, see a Black person on the street, and say “Wakanda forever.” When that happens, I always wish they’d say back, “forever-ever?”