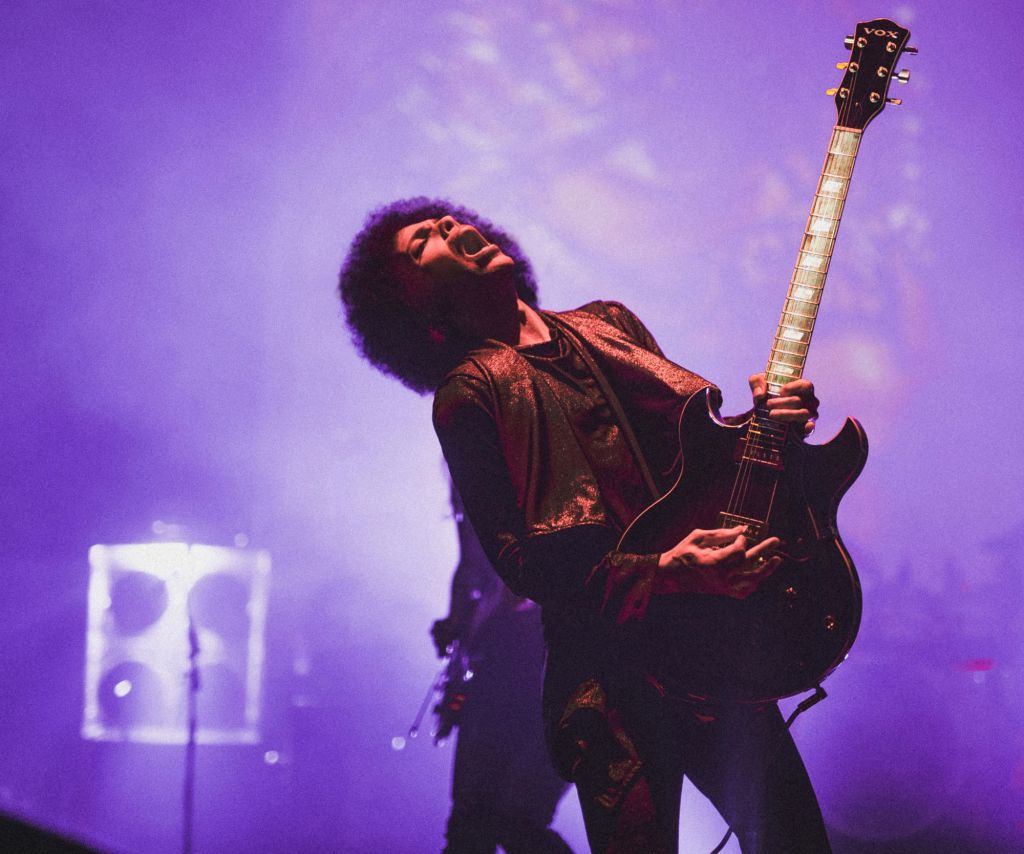

Source: Getty Images / Getty

There’s no doubt Prince was one of the most outstanding entertainers of our time. But in discussing his contributions to the world, one would be remiss to fail to also examine his role within Black culture—not just as a musician, but as a figure within Black labor movements and an advocate of social consciousness.

From May 24-26, the world’s first academic conference devoted to Prince sought to explore this. Titled “Purple Reign: An Interdisciplinary Conference on the Life and Legacy of Prince,” the three-day event called for scholars from all over to meet in England and analyze what Prince actually meant.

“Prince is Black,” Zaheer Ali, Adjunct Instructor at NYU, told CASSIUS. “And I don’t mean that in any kind of flippant way; I mean in terms of his conversance and integration into the community and its traditions and culture and politics.” Ali—who attended and spoke during the conference at the University of Salford—worked with author and social justice scholar Monique Morris and Dereca Blackmon, Associate Dean and Director of the Diversity and First-Gen Office at Stanford University, on a panel called “Free the Slave: Prince and the Black Freedom Movement.”

“We informed a lot of scholars around Black tradition who hadn’t really understood that, who we actually challenged in meetings [and] in panels around using the phrase ‘Prince transcended race,'” Blackmon added. “We talked about the white supremacist notion that Blackness would be so confining.”

CASSIUS spoke to Ali, Blackmon and Morris about their panel, what it means to be a Black artist in 2017, and what they hope to achieve through their work to explicate Prince’s narrative.

“Prince had a lot to say,” Ali continued. “And if you don’t have that frame of reference of the Black freedom movement, you might miss it if you just listen to Prince. If you’re not familiar with Prince but you are familiar with the Black freedom movement, you’ll miss Prince. That’s the gap we’re trying to bridge.”

CASSIUS: Is this the first academic conference devoted to Prince in the world?

ZAHEER ALI: I guess we could say devoted solely to Prince. In January, Yale had a conference on Prince and David Bowie, but this one was the first one devoted solely to Prince.

C.: How did it come together and how did you all become involved?

MONIQUE MORRIS: The University of Salford sent out a call for papers and an invitation to scholars to really prepare papers and engage in an interdisciplinary conversation about Prince. Zaheer, Dereca and I have known each other and of each other for years in terms of our appreciation for Prince. Zaheer teaches a class at NYU on Prince and Dereca’s about to teach a course on Prince at Stanford. I have had the opportunity to work with and engage with people who have worked closely with Prince and all of us have been lifelong fans and enthusiasts for the multifaceted way in which Prince engaged his art. I think that for us it was almost a natural way for us to explore a dimension of Prince’s identity and art that is often obscured by other presentations of his contributions to our culture, and so we wanted to prepare a discussion that gave us a chance to really dig a little deep and as deep as we can get in an hour and a half [laughs]. Just to present something that gives the public and particularly the academy some grounding in Prince’s contributions and connections to Black labor movements and forms of expression and theology and to just sort of uproot the conversation in that.

DERECA BLACKMON: I would just add that I think one of the things that was really special about the conference – I won’t speak for the other two folks on the phone – but I know for me ever since Prince’s death, there’s been so many articles written, so many events, so many parties and it’s been hard as a person who really has been more deeply considerate of his work, not just in music but outside of music to really feel like there isn’t something that really honored the fullness of his contributions to Black lives specifically, but to sort of the general community overall, and so what was exciting about this invitation is that it was an opportunity to really be with other people who were looking at his body of work and his artistry from a deeper, more comprehensive lens.

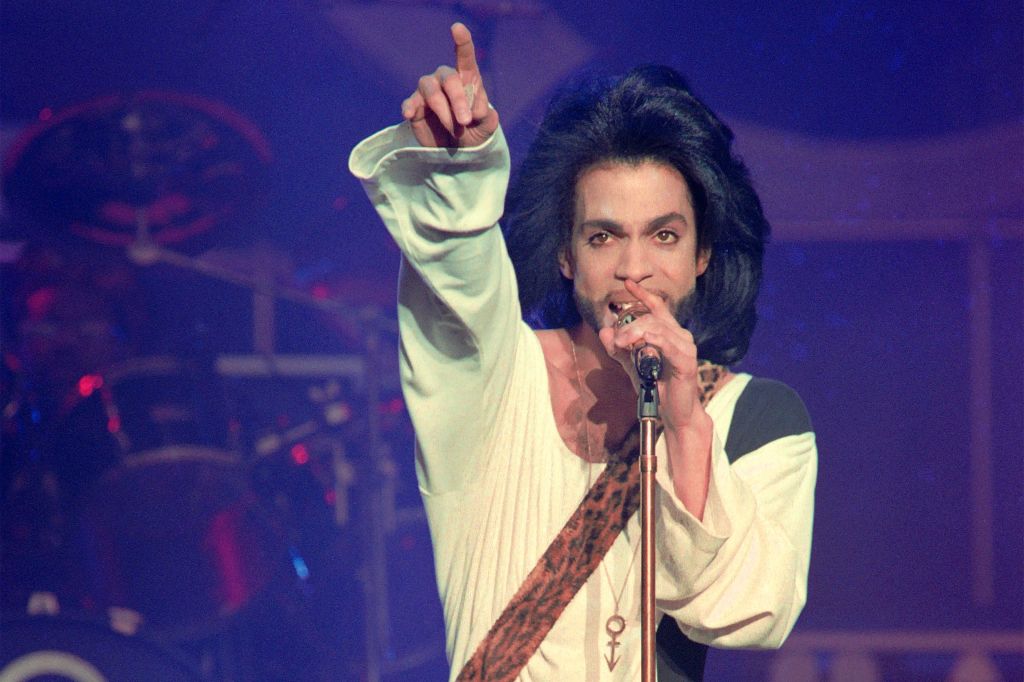

Source: Rob Verhorst / Getty

C.: Monique, I think it was you who wrote that you guys are basically “reclaiming his Blackness.” Can you expound on that idea a bit? What does it mean to reclaim Prince’s Blackness?

MM: Yeah, that was definitely shorthand [laughs]. I’ll speak for myself, but I think we shared a pleasant pride in seeing a good number of African Americans there in England talking about Prince’s engagement with Black communities, engagement with Black critical thoughts, engagement with Black political movements and social consciousness. Our intent was really to make sure in conversations about someone so fantastic and beloved by so many communities that we talk about his contributions and his identity in the context of Black mobility, creativity, engagement, consciousness, because people tend to talk about it as something exceptional to Blackness rather than a part of Blackness. What we wanted to do was really engage in a more robust call for the appreciation of Prince and his music, but also the things he did outside of the studio and the way that he talked to us through music about conditions outside of the studio that were absolutely rooted in this Black experience in the United States.

ZA: I would add there’s this tension with talking about somebody like Prince—because he was so exceptional, because he was so unique. There is this risk to kind of hermetically seal him off from his time, from his people, from his community, from the political traditions that informed him and that he informed. What we were trying to do is contextualize him and establish those connections that yeah, he was one of a kind, but he was also part of a community. I think that is the challenge with somebody like Prince. You have people who are not familiar with the tradition of, say, the Black freedom movement or the Black radical tradition or Black liberation theology [who don’t] see those elements in his work. But you also have people who are familiar with those traditions, but not familiar with Prince and kind of write him off or dismiss him as some kind of pop star—a kind of empty, superficial musician who just wore lace on stage—[and don’t have an] understanding [of] how he had some very critical and important things to say that reflected his engagement with tradition.

C.:And you all led presentations within this panel. Can you each give a synopsis of what you respectively spoke about?

DB: My piece was around Prince’s Black liberation theology and, to the point that Zaheer made, what was really exciting for me is that as I reviewed the core tenants of Black liberation theology, it became so obvious with each and every one the way this context really perfectly held the work that Prince was doing. I started talking a little bit about my own experience being from Detroit and being someone who listened to Prince from 1981 as a young middle schooler and talking about what it meant to be a witness to The Electrifying Mojo, who is a DJ in Detroit that played Prince for hours at a time on a regular basis and scored the first live interview with Prince. In terms of the idea that Prince was involved in the liberation of Black music, what was happening with Mojo at that time was that he was also breaking artists like the B-52s and Kraftwerk and the J. Geils Band. What I was explaining to the audience was that people think what Prince was doing was so outside of Black music, but here you are in this primary Black market, where one of the most successful DJs is playing all this wide variety of music. I talked about that and then moved into looking at the liberation of Black masculinity and the ways in which that had been sort of put into a box of what a Black man can be. I also talked about theology and the way the world saw Prince as so extreme and radical around being able to put spiritual messages in his music. Lastly, I talked about Prince and the liberation of Black people, and this is where we got into his philanthropy that was largely behind the scenes. We now know a lot about what he did with Van Jones and the Green Economy, with Tavis Smiley, with Black Lives Matter, Trayvon Martin, Baltimore. But even going way back he was involved with Marva Collins and [her] college preparatory school in Chicago. He was never operating outside of Blackness.

‘He was being authentically himself in a way that some of us could recognize and appreciate, some of us could love and adore, and others of us tried to emulate because we understood it as an absolute reflection of the things we’re all capable of.’

ZA: My paper was titled “Slave to the System: Prince and the Black Radical Tradition.” Famously, or infamously, in 1994, Prince began appearing with the word “slave” written across his face, and many people dismissed him and what he did as an act of petulance. Here’s a multimillion dollar rock star who just signed a multimillion dollar contract with a record company, Warner Brothers, complaining—“whining,” one writer wrote—by calling himself slave. What I did with my presentation was examine that moment in Prince’s work and life in a broader context of Black labor protest, how even the invocation of slavery was very common in Black discursive traditions, how Black people talked about exploitation by making historical reference to slavery, and then talked about how that sharpened Prince’s own critique of racial capitalism—especially as it was practiced in the record industry. Black labor and Black creatives’ work was expropriated and exploited by the music industry, leaving Black workers as artists [and] Black artists as workers, with very little control over the means of production, very little ownership over what they produced, and very little resources or benefit from what they produced in the long run. I looked at how that moment kind of crystalized and highlighted the ways that Prince had always focused on the concerns of work and workers, whether it is the kind of leisure anti-work protest of the song “Let’s Work” or lyrics in songs like “Raspberry Beret”: “working part-time at a five-and-dime, my boss was Mr. McGee. He told me several times he didn’t like my kind ‘cause I was a bit too leisurely.”

C.: Monique, and you touched upon Prince reclaiming his music masters?

MM: Right. My paper was titled “Walking in Crooked Shoes: Prince and the Complication of Mastery,” because what I wanted to do was explore mastery in the context of freedom, really picking up from the themes that had been laid out before my presentation and picking up with the idea of his engagement, of this idea of being enslaved by a system or enslaved by a consciousness of oppression [leading] him to a reframing of what it would require to actually be free. My paper talked more about the public manifestations of his exploration with this conflict with mastery, both in terms of how he would use his own leverage to support the development of other artists, but also the preservation of spaces where Black music and art had been created. I talked a bit about how he did help to save the forum in Los Angeles and talked about it as this historical site of music, his own public engagement around this notion of what it means to free the slaves and how that means that one has to engage in a mastery of self in order to move beyond just the creation and production of art and the creation of music but really to become one’s art and music such that the notion of freedom becomes internalized and very easily then comes to reject this notion of oppression and exploitation. I talked a bit more in review with some organizers who had worked with Prince for a long time, both in the reclamation of his masters, but also really in his support for Black Lives Matter. The heart of my presentation was around this concept of mastery and the value of Black lives and how he came to articulate that both as a presentation of mastering oneself but also the understanding that a mastery of self means a mastery of community, and how that became a part of his work, his demonstration of excellence—the way that he openly challenged police brutality and stood in support of the Black Lives Matter movement here in the U.S., and how he was able to use his music and his stature to advance a narrative of freedom that would embrace women, embrace Black, brown and queer people, and to not just talk about it, but actually engage them as thought partners and folks in his world, in many different dimensions. My conversation was about the leadership of the freedom movement [and the] engagement and visualization of that as something that must support the divine feminine energy and contributions to this work and to see that as a mastery of oneself toward the realization of freedom.

Source: BERTRAND GUAY / Getty

C.: Absolutely. I’m also thinking about how Prince removed his music from streaming services within that reclamation versus how someone like Chance the Rapper claims ownership of his music via his independence, but then also still won a Grammy. What does it mean to release music as a Black artist in 2017 versus what it meant during Prince’s time?

DB: I think one of the things I would say about that is we all sort of acknowledge that the kind of freedom that Prince had is incredibly rare, if not impossible today to imagine: a 20-year-old in the studio saying, “I’m gonna produce every part of this album” and getting support to do that for multiple albums. But I think that he’s still that lever which people can advocate for that because he was so successful in that model. I think a lot of what Zaheer talked about and what Monique and others have talked about is that he really endeavored to open the doors for more people behind him to be able to do that, but when you look at Tidal and streaming services and some of the things that Beyoncé’s been able to do to sort of circumvent the constraints of the music industry, I think there are still people around today, they just tend to be more powerful. But then you also have to look at the mixtape movement. From Master P on, there were always people who said, “We’re gonna produce and distribute our own music.” We have people who are breaking from YouTube. Independent artists are always gonna find ways to break out of the boxes that the music industry creates.

ZA: I think what Dereca said was right on point. Prince, he has this verse in one of his deep cuts called “Don’t Play Me” and the line goes, “Been to the mountaintop, it ain’t what you say,” and this is someone who had reached a pinnacle by all measures of critical, commercial success, and he walked away from it. He walked away from it by not only protesting his record company, but changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol. This very much challenged the way his music could be marketed and this was something he was consistently challenging—the logic of the marketplace when it came to how it reduced the labor and work of Black artists to this kind of commodity that was separated from them so that it could be easily bought and sold. To the degree that Prince could use the internet as part of his own journey of freedom, he did. But then he realized that the internet had succumbed to the market logic as well, and he famously said “the internet is dead.” Not that it was dead, but it would no longer be able to do or could do what many people envisioned it being able to do in terms of freeing artists from the constraints of the logics and the markets of the record companies. I think he always recognized that he was in the position to do that in a way that he had built up a name for himself with the help of Warner Brothers. He said, “Yes, what we had worked for the time we worked it, but then we reached a point where it didn’t work.” He recognized that he had the kind of stature that allowed him to challenge and be outside of the machine and mechanisms of the industry. I think it’s remarkable that someone like Chance was able to win an award without having an official release. I think part of that has to do with the actual work that someone is doing, the art that speaks for itself. That is very much in the tradition of someone like Prince. In his history I think there are many lessons that people will continue to learn.

MM: That’s why I thought it was important to engage this conversation about being true to oneself, knowing oneself, and creating art that is a reflection of oneself. That takes a certain amount of freedom, right? It also takes a certain amount of mastery and understanding of what is required to bring your whole self to this work. In advocacy in the justice space, in the teaching space, we always talk about bringing your whole self to an inquiry or bringing your whole self to the work as a liberation practice. In many ways, that’s exactly what [Prince] was demonstrating for us. While we were on Monday, he was still on Friday trying to figure out what he was doing. He was being authentically himself in a way that some of us could recognize and appreciate, some of us could love and adore, and others of us tried to emulate because we understood it as an absolute reflection of the things we’re all capable of. Artists today are challenged to embrace and rise to that level.