Source: Pool LEFRANC US / Getty

Very few queer African-Americans left reports on their desires in the Jim Crow South. And yet, despite the mainstream claims that homosexuality is a recent enigma, Shoga Films’ documentary, Queer Harlem Renaissance: A Prospectus, is fighting to re-establish the history of Black Queerness and its struggle against the Black Elite’s steady social concessions for the White mainstream.

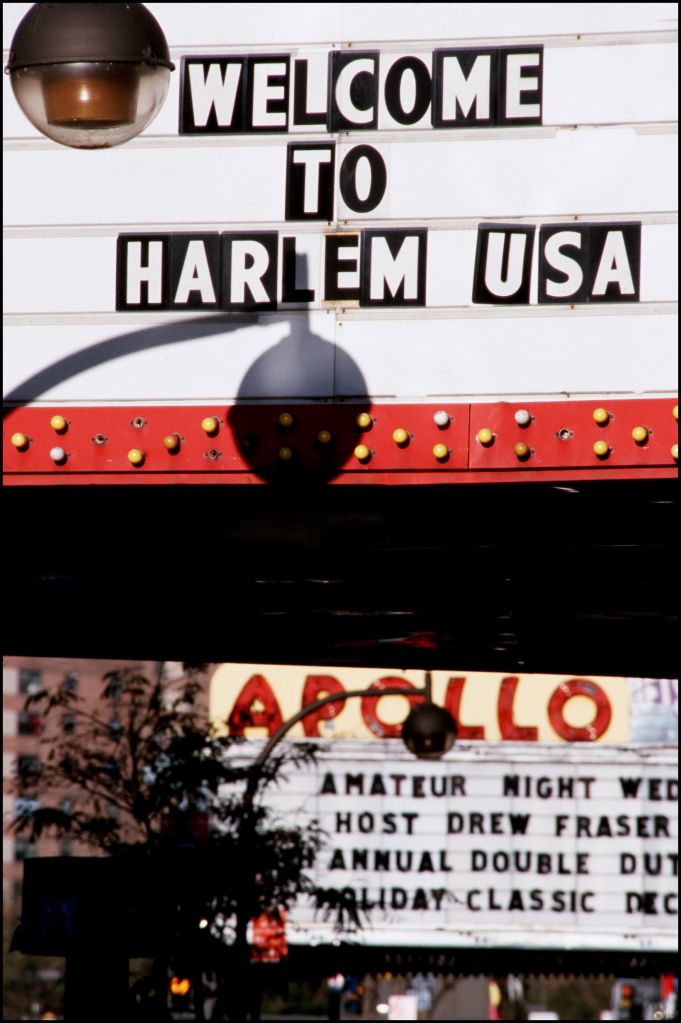

A century ago, Black culture’s acceptance of homosexuality was just another argument against the Negroes’ campaign for “model minority,” and one-time homosexual mecca, New York, was ground zero for these differing Black realities and experiences matriculating from the Jim Crow. Of which, Harlem’s many working-class artists held sovereignty but were still beholden to the conservative expectation and approval of Harlem’s elite African-Americans.

Niggerati Manor, the rooming house for the Niggerati, rested at 267 West 136th Street (where Thurman and Hughes lived), before being burned down. Wallace Thurman, the founder of the Niggerati, began the group as a counter to the “society Negroes” whose mainstream pursuits for white acceptance often felt like a handicap to African-American advancement.,

The Niggerati’s two greatest works: FIRE!! And Harlem, only lasted a single issue respectively due to the on-going issue that plagues many structures: finances and time. Both issues stuck to themes Alain Locke, a discreet gay African-American writer and activist, deemed “effeminizing” and scandalous.

Understandably so. As much as FIRE!! was a social mockery of Alain Locke’s contemporaries and supporters in the Black Elite, FIRE!!’s younger sister, Harlem, fought to be politically oriented and more commercial in approach.

Today, Shoga Films has evolved to challenge the Black Elite’s misconception of Queerness over the course of a wildly successful century in Black History. And, as Khalil Sullivan, Artist-in-Residence for Shoga Films, has found: Black culture is in desperate need of remembering. And Remembrance is found through two of Queer Harlem Renaissance’s most shock-inducing subjects: Richard Bruce Nugent, and the Niggerati Manor.

Cassius Life: How do you think the vision of Niggerati Manor and turmoil that it had to overcome for the issue to live reflects the struggles of artists today?

Khalil Sullivan: Most artists are working-class or work other jobs. There’s a small coterie–say a 1%–who are immensely wealthy from their careers.

In regards to Fire!!, we can look to Wallace Thurman’s novel Infants of the Spring or portions of Bruce Nugent’s posthumous novel Gentleman Jigger, both fictionalize the genesis and failure of Niggerati Manor and Fire!! The Cabaret School of Harlem Renaissance artists struggled with earning a living wage from their art, just like artists of today. Thurman’s novel is a sort of rumination on precisely why Fire!! failed: audiences weren’t ready to openly support these types of black stories. I’d argue that this has less to do with mismanagement and more to do with the ugly reality of earning a living wage as an artist-of-color under capitalism.

Both Thurman and Nugent became increasingly aware that they would have to “sell-out” or perform the vision of blackness that mainstream/white audiences wanted to see. This is the conundrum they faced. Fire!!’s failure taught them a valuable lesson. But it didn’t solve the problem.

Capitalism loves exploitation. And in the West, that exploitation involves people of color and women, queers and sex workers, enslaved peoples, and the working class. To be an artist who speaks to being black and queer and poor…well, that’s going to be a challenge, because those communities don’t often own the means of production and distribution. White supremacy won’t allow it. Take for example, the Black Swan record label, first of its kind created during the Harlem Renaissance. It had quick success but also quick failure, partly because it had to depend upon white-owned record manufacturing plants to press its records.

The internet has begun to untangle some of the dominant culture’s grip on distribution (how artists connect and interact with their audiences). Twenty-first-century art is exploding, and the explosion is messy, fun, and wonderful. Younger, neophyte artists can build support online as well as face-to-face. The online tools are a powerful new addition.

But, during the 1920s, black artists couldn’t depend upon black patronage to make a living wage; black audiences are not monolithic in their adoration of black art. Not to mention, black audiences battled with their own internalization of white supremacist ideals in relation to what is good or bad art. And, as I said before, the cultural industry was dominated by White Americans, many of whom operated with both conscious and unconscious bias. The difficulties faced by black artists in the 1920s were remarkably different because the forms and distribution of capital were different.

The symbolic wealth, the forms of dandyism, in which black artists perform their subjectivity in today’s landscape has more to do with protest–a protest against the denigration of the black body and black culture. When black artists speak on or perform with various symbols of wealth, they are taking part in a long tradition of signification. Blackness has long been associated with a number of stereotypes, everything from hypersexuality, hypercriminality, laziness, ignorance, servitude, slavery, et cetera. However, when black artists work against these stereotypes, to diametrically oppose them, they are performing resistance. Even when black artists take up these stereotypes, just to have fun with them, they are using agency to control their own narratives. It’s a beautiful and powerful statement against Negrophobia and white supremacy. It is a reclamation of the body, not in service of white supremacy, but in service of each person’s own desires that flies in the face of centuries of dehumanizing treatment under capitalism.

CL: When conceiving of the Docuseries, what was the most important message that you felt Nugent and the Niggerati Manor explained about the Queer Harlem Renaissance? Why was this story at the forefront of history when considering so many names that played a role into what we know is Black and Queer and Black Queer History today?

KS: Modern audiences–whether queer or heterosexual–will easily resonate with Bruce Nugent, because he lived an unabashedly queer life. He was out. Today’s audiences understand what the closet means, even though there’s still more to do to unpack the implications of living life in secrecy. Nevertheless, we have a framework for understanding Nugent’s life choices.

Unfortunately, he didn’t leave behind a large body of work, even his only novel was published posthumously–probably because it was so open in its depiction of interracial relationships and sex between men. In Nugent, we find a critical problem that he explored in his work. How does one negotiate being both Black and queer? How does one exist as bi-racial or even multi-racial? How does one develop a class consciousness? How do black people find beauty and pride in their own subjectivity, amidst a culture that fetishizes and simultaneously demonized blackness?

CL: Where do you believe the influences of the Queer Harlem Renaissance can assist in the forward momentum of Queer/Black works in the future?

KS: There’s something to be said for making “real” the previously buried, marginalized, and silenced histories of queer Harlem Renaissance artists. That kind of revisionist work is recuperative and fulfilling for specific communities (black and queer), but we hope, it’s instructive for allies, as well. As Eve Sedgwick notes in Epistemology of the Closet, the cultural renaissances of Europe would be nothing without the queer artists who made those movements possible. The same can be said for the Harlem Renaissance.

CL: What do you feel is still constantly being misunderstood about the Harlem Renaissance and Black History overall despite the many attempts to advocate and manifest the found and cherished realities of these pivotal persons and movements?

KS: Undoubtedly, there’s a great deal of information that does not reach mainstream audiences. Scholars, independent researchers, and folks invested in keeping the tradition of the black arts alive know about Harlem’s legacy. In the interest of appealing to educators, parents, the larger LGBTQIA family, and more, we work in film. It’s a medium with which we are all familiar.

To see the history of queer black artists in film, colorized, complete with music, style, and dance is help individuals get an immediate sense of the importance of queer subjects within history. To hear their words is to understand how incredibly attune queer, Black artists were to the complexities of modern life in America.

Shoga Films is committed to bringing those words to life, playing the songs, sharing the histories, and we believe audiences will be able to create the vital connections they need.

CL: Was there something about the Queer Harlem Renaissance that you felt similarly explores the nature of your past conversations Shoga Film’s has explored in queer, Black America?

KS: Absolutely. Queer Harlem Renaissance artists were engaged in many conversations, not just about sex and sexuality, but also intersectionality, passing, code-switching, multi-racial subjectivity and families, class bias, colorism–all the concepts that people of color and queer folk have been discussing and engaging in. As artists they found ways to bring those conversations into their work. It was a groundswell of activity, unlike any other in US American history.

CL: Do you think the views on the content of Niggerati Manor’s Harlem and FIRE!! Were the norm of the era, or do you believe that this group were speaking on things that were discreetly predominant for the time?

KS: Those topics were the norm–that’s a truth. But it was a closeted norm. Everyone knew about sex work, queer sexuality, non-traditional ways of being, but those things were not openly discussed. If they were, the discussion was problematic. For example, gay and lesbian sexualities were seen through a narrow prism of gender inversion.

Fire!! proposed that we burn down those preconceived notions. The “Cabaret School” artists of the Renaissance, to borrow Shane Vogel’s term, wanted others to investigate the various forms of bias that were alive in the minds of the black community. Forms of bias that were alive in the larger American psyche, I dare say.

It may be easier if we understand the relationship between the Cabaret School–Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, Bruce Nugent, Wallace Thurman, and Langston Hughes–alongside white allies like Carl Van Vechten or even the Bohemian set of artists who congregated in other parts of New York. They were progressive. A bunch of artists daring to depict and say what most folk were too scared to say on their own, even if those stories were secretly very entertaining.

CL: In a contemporary world, do you see the concerns of the Niggerati Manor that were issued in these challenges validated?

KS: Absolutely. Many of the Harlem Renaissance’s artists were ahead of their time. They were vanguards. Courageous artists, speaking their truth the best they could. That’s why we continue to lift up their art.